Team Covenant are among the leading experts on customizable card games, with over 14 years of experience playing them, selling them, and running organized play events. Last year they released a series of podcasts titled “How to Ruin a Game”, where Steven and Zach (S&Z) discuss past customizable card games and why they disappeared from player’s minds and gaming tables. Here I cover the first part, “First Principles”. You can listen to the original podcast here.

What are First Principles?

First principles are the design heart of the game: what are the players trying to do and how are they doing it, the core of what the game is all about. According to S&Z, as the game develops, designers move away from the first principles. This can be a slow process, where a set of mechanics are slowly introduced over a time period and the complex constructed environment culminates in divergent gameplay. Alternatively, it could be an abrupt introduction of a new card or cards that “break” the way players have interacted with the game so far. Either way, the result is loss of identity. The game becomes something else, different from what most players have enjoyed. Players become disillusioned and leave.

The Tale of the "Radisson Cheese Plate"

S&Z give two examples for games that lost their first principles. The first is Android: Netrunner, an asymmetric cyberpunk game, where the players take either the Corp side or the runner side. The Corp is defending their board and advancing agenda cards for points, while the runner builds a rig of hardware and programs and attacks (“make runs”) against the Corp to steal those same agendas. Android: Netrunner has three first principles:

- Tension between the Corp installing and scoring agendas and the runner stealing them

- The Corp using meaningful Ice cards to protect their board while the runner is breaking through using different tools

- Managing risk (installing agendas or running) through resources (cards, clicks, and credits)

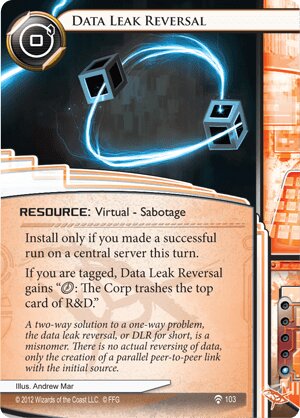

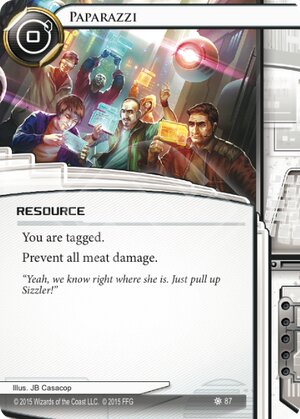

That all changed in August and September of 2015, with the release of Paparazzai and Wireless Net Pavilion. Paparazzai allows the runner to tag themselves free of charge while protecting them from damage, nullifying one of the Corp’s punishment mechanics. Wireless Net Pavilion adds an additional cost to the Corp’s trash resources action and can be played in multiples for a crushing tax. Once the runner got all three cards on the table, the game’s first principles disappear:

- The runner no longer needs to steal agendas, instead trashing the Corp’s deck

- Ice is meaningless since the runner does not run anymore

- The runner does not spend resources any longer and does not deal with any risk

The end result was the “Radisson Cheese Plate” deck that won the 2015 Android: Netrunner Worlds Championship. It created a frustrating game experience for the Corp player, as all of their game mechanics are ignored and they cannot do anything to stop the runner from winning.

The Most Boring Boxing Match

I want to thank Erik Johnson for his help with Star Wars: Destiny history!

The next example S&Z provide is Star Wars: Destiny, a collectible card-and-dice game where you get to build your dream team from across Star Wars history and duel with your opponent. The Destiny first principle is that gameplay is swift and intense. Players rapidly alternate taking actions and trading blows, giving the feeling of a boxing match. Typically, each player can only take a single action before their opponent gets a chance to respond in kind. In particular, you activate a card (such as rolling the dice on a character), your opponent gets to do something, you resolve a die or dice, your opponent gets to do something, and so on.

The game’s rules include one notable exception to this with the “Ambush” mechanic. After you play a card with ambush, you may take one additional action. It often appears on weapons, allowing you to play the weapon and immediately activate it. Thematically, it represents surprising your opponent with a hidden weapon.

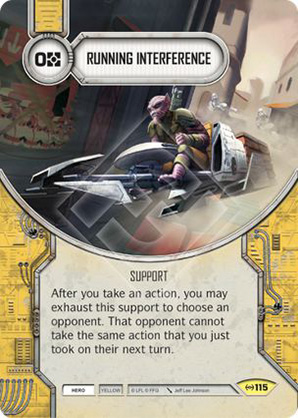

Once again, a new card radically twisted an existing mechanic. In this particular case, Sabine Wren was to blame. Sabine Wren says that before you activate them, you may play a weapon from your discard pile without spending the action. Ambush was designed to require an action (play the card) and then give you an action. With Sabine, you do not pay the action upfront. Effectively, you gain a free action, usually activating Sabine and resolving their dice before your opponent can interact. The problem is exacerbated by Running Interference, which stops your opponent from repeating the action type you took. Activating and resolving are the two most important actions in the game and nullifying them completely incapacitates your opponent. The combination of these cards turns Star Wars: Destiny from a tense boxing match into a sad display where one player pummels the other.

Rules are Meant to be Broken

I agree with S&Z that sticking to first principles is crucial for maintaining a healthy play environment. With that said, I love card games because of the feeling of looking at a new card and thinking, “Wow, this is awesome! How did they dare print this?”

Going back to Android: Netrunner, this kind of inventiveness is baked into the DNA of the game. For example, each player starts the game with an identity card, and many have abilities that radically change the game. Two of my favorite identities, Nasir Meidan: Cyber Explorer and Apex: Invasive Predator, completely change the resource dynamic on the runner side. Another cool mechanic is “Public” agendas such as Oaktown Renovation: Corps usually install agendas face down, but when going public they forfeit on that hidden element in exchange for immediate rewards.

As card game designers, we are walking on thin ice. Stay within the confines of the game’s initial release and players get bored. Experiment, and risk breaking the game and alienating players.

Keeping Your First Principles Intact

One of S&Z’s insights is on how collectible (booster-based) card games differ from other games in the genre through the availability of limited formats. Even if the constructed environment suffers from problematic interactions, players always have sealed and draft as a resort to enjoying their favorite game. In my opinion, non-collectible games can and shouldoffer limited formats as well. Worldbreakers, my upcoming two-player card game, is designed for cube drafts: even if a particular card or interaction is problematic, players are less likely to get it (especially if their opponent is mindful of it and grabs one or two key pieces!)

The Worldbreakers two-player draft mode is available for free on Tabletopia! Check out the “How to Play” video to learn more.

I would like to take this a step further: more formats are good. Magic: the Gathering is known for its plethora of formats, some of which have a rotating card pool while others are eternal. Modern Netrunner (under the NISEI fan-run organization) has five formats: Startup, Standard, Snapshot, Eternal, and the recently-introduced Random Access Memories. Players love options that help them play the game the way that they enjoy it.

Another set of tools in the designer’s arsenal are bans, restrictions, and card nerfs. Star Wars: Destiny had both bans and nerfs throughout its lifetime, including many changes to cards in the Sabine Wren deck I described above (for example, Running Interface was changed from a recurring ability to a one-time effect). Early in Android: Netrunner’s life, Fantasy Flight Games introduced the NAPD Most Wanted list, where some problematic cards were more expensive to include in your deck. This was later extended to a banned and restricted list by NISEI. However, changing an existing card is tricky. Ban it and players are angry that they cannot use the card they paid you money for. Nerf it, and now the cardboard is different from the game effect. Magic: the Gathering has become notorious for this issue with the introduction of ten Companion cards in the Ikoria: Lair of Behemoths expansion. The mechanic was so powerful that it subverted Vintage, Magic’s oldest and most powerful format. The Companion text was changed, confusing players and even interfering with limited formats, which are supposedly immune to bans.

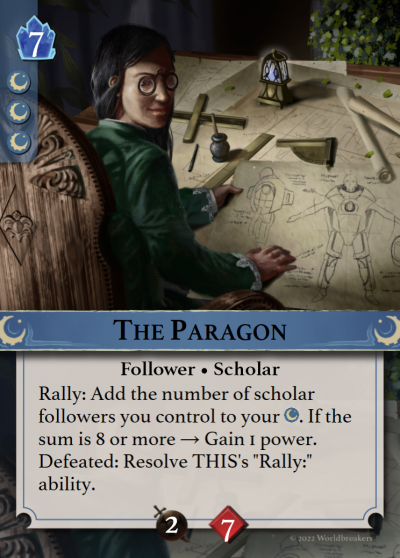

One last note I want to mention is that you can start with carefully experiment with new ideas, then potentially expand on them when they are tested by the player community. In Worldbreakers, players typically gain power (the points that win the game) by developing location cards or by attacking their opponent with followers. Advent of the Khanate, the Worldbreakers core set, has a single card that breaks that mold: The Paragon, which allows you to slowly gain points at the end of your turn. The Paragon is expensive, can only be played late in the game, has a difficult trigger condition, and only gains you one power a turn. There are many precautions in play to make sure that she does not spiral out of control. This allowed me to introduce the idea of alternative ways to gain power while still sticking to the Worldbreakers first principles.

My favorite quote from the podcast is that you should understand the first principles of your game. This is different from being timid and avoiding meddling. Vice versa, you should experiment all the time, but keep in mind what the players love about your game. Even when you color outside of the lines, the overall picture should be clear.

Thank you for reading! If you like card games, please check out Worldbreakers, my upcoming two-player card game. Worldbreakers is unique in its design around two-player cube draft. Play on Tabletopia, join the Discord to find fellow players, and subscribe to the mailing list to hear about the latest design dairies.

Great write-up! The most egregious of those examples is the companion cards in Magic. Given how much experience the designers of that game have, it’s strange that could foresee the problems in advance. Often it’s difficult if not impossible to foresee all possible card interactions, especially when the cardpool is vast, but the problems with Mtg’s companions were obvious to many even before the set was released.

Agreed, I played Companions in draft and it was clear that they are a problem. I wonder what is the story behind them slipping through WotC’s playtest — they’re pretty egregious. While I loved Yorion, I’m glad that all of them rotated out of Standard.

I agree these are examples in which card games were broken. However, I do not think they have anything to do with betraying the so-called first principles of any particular game. There is a more fundamental explanation. Every example you provided is a case in which a player is deprived of agency prior to the official conclusion of the game.

Win or lose, players want to play. Consider a game like basketball. A player wants to dribble, run, shoot, and defend. That can be fun even if the score is lopsided. But imagine playing against an opponent so good they always immediately steal the ball and dunk it. That’s not fun for either team. One team has completely lost agency. Not only can they not win, they can’t even play. The other team wins, but they’re also hardly playing.

The other related problem is a misalignment of the victory condition and the end condition. Pong/Tennis has the perfect design in this regard. If a game of Pong is not officially over, then both players still have a chance to win. As soon as a player’s chance of winning reduces to 0%, then the game officially ends. There is no so-called “garbage time” whatsoever.

The M:tG Channel example above doesn’t have this problem. If you get hit with Channel/Fireball, the game is over. But the Data Leak Reversal suffers from this big time. As soon as a player has the combo set up, the game is effectively over, but it is not officially over. Without hardly any chance of victory the corp player must sit there and wait to lose (or forfeit). During that time they have no agency and can’t even have fun playing. If the game had simply mercifully ended officially, it would have been better than making both players sit there and wait for the R&D to run out.

TL;DR: Yes, the games were broken. I don’t believe “first principles” is the correct explanation. The lessons to learn when designing any game of any kind are

1) A game state in which one or more players loses all or most of their agency (ability to play) should never be possible under any circumstance.

2) The victory condition and game ending conditions should always be in alignment to eliminate garbage time.

I agree with everything you said. I think that from a theoretical perspective, there are different ways to explain why these particular interactions were problematic. Both the “First principles” explanation from Team Covenant and your “garbage time”/agency framing seem reasonable to me.

In particular, your point about the game being effectively over but not officially over is quite a design challenge. One of the things I liked about Netrunner (and which DLR broke) is that both sides always had a chance to win, no matter how slim. This is unlike Magic: the Gathering (or Hearthstone), where games often end with a concession, NOT with a player going down to 0 life/health.

I think a more relevant M:tG example is the current “Izzet Turns” deck in Standard where players copy Alrund’s Epiphany with Galvanic Iteration to take 5 or 6 turns in a row as early as Turn 6. That is the purest violation of #1 you list in your comment, as the other player has lost most of their agency on their opponent’s turn, and surely all of it by their first additional turn.